Arturo Aguirre Moreno

Abstract

This article explores contemporary violence in Mexico from the theoretical proposal of forensic philosophy. The approach is from a spatial event: the clandestine common grave. It refers to twelve years of an intrahistory of violence in the face of a conflict that has grown in lethal intensity, which requires the theoretical, as well as vital, construction of a critical space on suffering experiences. A minimal analysis of comparative cultural theory of life is carried out as a spatial structure of human production. Violence, within the framework of knowledge with a philosophical approach emphasizes the basis of a space qualitatively constructed on social sufferings and the disarticulation of links between the living, and of these with their dead.

Keywords: Conflicts, Social Philosophy, Common Graves, Mexico, War against Drug Trafficking, Forensic Philosophy.

Resumen

Este artículo explora la violencia contemporánea en México a partir de la propuesta teórica de la filosofía forense. Se aborda desde un evento espacial: la fosa común clandestina. Se refiere a doce años de una intrahistoria de la violencia frente a un conflicto que ha crecido en intensidad, lo que requiere la construcción teórica y vital de un espacio crítico sobre experiencias de sufrimiento. Se realiza un análisis mínimo de la teoría cultural comparativa de la vida como una estructura espacial de la producción humana. La violencia, en el marco del conocimiento con un enfoque filosófico enfatiza la base de un espacio construido cualitativamente sobre los sufrimientos sociales y la desarticulación de los vínculos entre los vivos y de estos con sus muertos.

Palabras clave: Conflictos, filosofía social, fosas comunes, México, Guerra contra el narco, Filosofía forense.

Theorical Proposal: Forensic Philosophy[1]

Is the conceptual exploration developed from the theoretical, technical and practical analysis of the “material homicide violence” that occurs in contemporary Mexico?

This theorical proposal focuses on the interactionism of material violence that attends to social suffering, the ontological denigration of the body in the brutality administered by the perpetrators, restores the public dimension of mourning and the importance of death in an extreme fratricidal process of social hostility.

The target of the forensic philosophy is the contribution of critical elements for the legal, space-vital (reterritorialization) and political reconfiguration of present-day Mexico. It aspires that homicide and execution, as well as suffering —in massive dimensions and unprecedented intensities—, cease to be a topical issue in the same measure in which the favorable valuation of living, the memory of injustices and the reduction total of the homicidal death in Mexico.

Theoretical Development

Homicidal violence in public space is a problem that has grown in complexity in Mexico during the last 12 years, since the extraordinary process of what was called the war against drug trafficking began[2] and was continued under the nomination of the fight against organized crime by the Mexican Government authorities,[3] who triggered the State’s material forces exponentially, after the formal forces (actors, institutions and the legal, ministerial and conflict mediation dynamics) were overcome, in part by an accelerated state streamlining, typical of the last three decades.[4]

In this way, these last 12 years show an intrahistory of violence in Mexico without glory, without heroes and without end. Therefore, it is understandable that it is the recounting, rather than a goal or micro-story, which has allowed us to advance in the affirmation that what we are living exceeds, by far, the categorial experiences that, as a society and as academia, we had on hand to understand the intensified and unimaginable brutality of which we Mexicans have been witnesses, victims and victimizers.

The absence of a theoretical construction on the way to manage the changes, life and death,[5] but also the failure of hypotheses about the monopoly of force,[6] or the astringency of culture in relation to violent practices against the living and dead body[7] are some facts that speak of the limitations that could previously go unnoticed or be supported in the “academic branch”[8] that corrodes the universities of Mexico; but that nowadays the retraction of thought before these facts only aggravates the device that is generated in the complicity between knowledge, power and doing .[9]

In such a scenario, it should not be surprising, that statistics and news information are those that have taken the lead role in these dozen years, to allow us to see what violence does,[10] when our criteria to question what violence is fails. This has several reasons, but one could be that of the profound historical lack, at least in philosophy, to think about contemporary violence in Mexico from an interpersonal damage approach, without justifications of the great history or structuralist and /or essentialist reductions, from constructs such as the community, the State and the sociopolitical enmity, which were offered by Modernity to make violence a valid, legitimate and/or recurring exercise.[11]

IMAGE BY MALCOLM LINTON, MÉXICO, 2013

Hence, to a large extent, we find studies on violence necessary today, as frontier knowledge, directed towards the development of situated knowledge, advanced and transformative, whose results contribute to the change and emergence of concepts, which promotes new approaches, the same as new agendas of knowledge in the understanding of violence. Knowledge that focuses its attention on agents, victims, factors, elements, multi-purpose, multi-causal and multi-factual relationships.

Notice, that events of violence generate, from within, new agendas of research both individually and in groups, because we are facing a map of activated terrors that increase not only in number, but also, their presence is extended in more locations in México.[12] A sequence of coerced disappearances, massacres, lynchings, femicides, human trafficking, forced displacements,[13] shows that which requests, or rather demands to be contemplated.

In the following pages, we will deal with reiterated violence, whose deployment shows an intensely particular registration code: with regards to clandestine graves. We speak of those graves found as well as others that remain hidden, uncountable and unthinkable, which make the augmentation of the conflict self-evident, as well as the transformation of executed violence, which in recent years has gone from rare incidents to the systematization of power and control of public space through death.

EJIDO EL PATROCINIO, OCTOBER 2016. PHOTO BY SIN EMBARGO JOURNAL

The records of clandestine graves in Mexico as a paralegal or illegal burial structure, promoted by territorial control conflicts amongst criminal organizations (that arranged complication and complicity of organized criminal gangs, State powers and business organizations), has been a fractal constant in the course of the 21st century. However, this second decade, which is not yet finished, is a turning point in this intra-history of violence; because clandestine graves in their multitudinous dimensions, but above all, because of the reiterated violence, have become a fact that is constantly present in the formation of the social space.

It should be noted that space is conceptualized here as a constructed space -meaning, that which is composed and created in company with others- and must be thought from the very term of con-struere insofar as it cannot be done by an isolated or lonesome individual.[14]

In fact, in the sphere of statistics and reports of clandestine graves, attention is drawn not only in the quantification or its qualitative features, but in the geographical differentiation, and although the events seem isolated through hundreds of kilometers between them, we speak of a politically limited geography between the Suchiate River and the Rio Grande; places where the practice of violence is repeated over and over, despite different factors, as well as reasons that can be enumerated to understand this problem.

In this sense, spatiality, in so far as structures of reference, are forms of correlation constructed to inhabit the world: house, territory, border, city, and so on. This construction, this way of creating space, between, is the way to be, to have and occupy a place as spatial realities that restore and reclaim space: a space that is built not only with magnitude but also with the sensory, the voice, the moan, the smell, the auditory, as well as the proximity and remoteness of others; therefore, space is not, in such way, a thing finished by others, but there are always relationships that can be continued, not made or modified by an insistent heterogeneous and dynamic us that makes space something common, as a shared form of being built.[15]

IMAGE BY MALCOLM LINTON, MÉXICO, 2013

Open to participatory intervention by the relationships and referentialities that it implies, then, the space facing violence is altered in its center of referentiality, in the way of physically inhabiting space;[16] for no place, not even our own place, is a simple construction, but a complex of links, networks, interactions and of spatial practices exchanges. Thus, in clandestine graves, an act of force-damage is evident in its execution as an organized and collective action, which modifies space, morphologically altering the spatial quality of the experience. Let us refer to the fact that clandestine mass graves are, again, not the product of an isolated individual, but part and sequence of a coerced disappearance scheme.

What are we talking about? In seven years, different punctual moments and concrete spaces of clandestine graves in Mexico have highlighted the reiterability of this structure to create the outline of our country our sorrowful space. From the period of 2007 to 2017, events that would suffice, each one by itself, [17] to form lines of work (theoretical research and social, political and cultural action) have emerged among us; however, various factors, actors and measures are those that intervene (either by deliberate action, by explicit resignation, or by measures that allow controlling and enhancing the affect and right of public mourning in unsuspected social dimensions).

MASS GRAVE IN VERACRUZ, MEXICO

This is the framework of unstable and chameleonic understanding (between speeches of epistemological, anthropological, historical, legal, forensic, political, ethical and aesthetic nature) that unfolds in the sequence and reiteration in the record of 1,143 graves; 3,230 bodies, present in 26 of the 32 states of the Republic, with approximately 20% of the bodies of the victims being identified, as featured in the Missing Persons and Clandestine Pits in Mexico Special Report between 2007 and 2016.[18] A report that comprises the period opened by the declared war against drug trafficking and the fight against organized crime, and that clearly warns, in itself, the limitations of its figures. In this way, the October 2016 report of the CNDH went through similar obstacles to those which journalist Karla Zabludovsky had experienced at the beginning of 2015 in obtaining truthful information, when she requested information from the 32 States on how many common graves there were in their territory since December 2006. The result is clear in the title of Zabludovsky’s report, published in an international media, in March 2015: “No one knows how many common graves there are in Mexico. Much less the Government”.[19] On its part, the report of the CNDH emphasizes that some state governments did not respond to the request for information from the agency, others did; given the lack of transparency, the agency crossed the information with a hemerographic sample, which our journalist followed during the previous year and a half: which allows us to provide approximate figures. But, with everything, and in fact, nobody knows how many common graves there are in Mexico.

SEEKERS OF COLECTIVO SOLECITO (FROM LEFT TO RIGHT: MARTHA GONZÁLEZ MENÉNDEZ AND ROSARIO SÁYAGO MONTOYA). THEY BURY THE ROD IN DEPTH WITH HAMMER BLOWS, THEN EXTRACT IT AND IN THE AROMA OF THE TIP OF THE INSTRUMENT THEY LOOK FOR THE VICTIMIZED BODIES IN THE AREA OF ILLEGAL BURIAL.

THIS PHOTO WAS TAKEN IN THE HILLS OF SANTA FE, VERACRUZ, MAY 10, 2018.

PHOTO BY DANIEL BEREHULAK, THE NEW YORK TIMES.

Let us recall that, in the location of most of the mass graves, between 2011 and 2017, it has been mostly by anonymous information that relatives and citizen initiatives have found the whereabouts of the graves mentioned above. Giving evidence of the collusion, the limitation, and the inability of the authorities at all levels of government and in all the powers that make up the grandiloquent “Supreme Power of the Union”.

Whatever the case, in the context of violent conflicts, the question that arises is whether this systematization and the high margins of damage evident in, produced, clandestine graves, are a worrying problem of insecurity or the feature of a conflict of larger dimensions, which is not reduced to crime, but which is not clarified as a process of civil war. Not being by means of ideology neither aspirations of political revolt or religious conflict, the malicious violence in the public space has characteristics of annihilation that operates from the hybrid generated by the economic capitalization,[20] the generation of confusing information -when there is – the political uses of the management of death and the retraction of the formal and material forces of the State in its governing bodies; all fueled by structural breaks of the cultural approaches to the valuation of life, the benignity over the body and condolence before the death of others.[21]

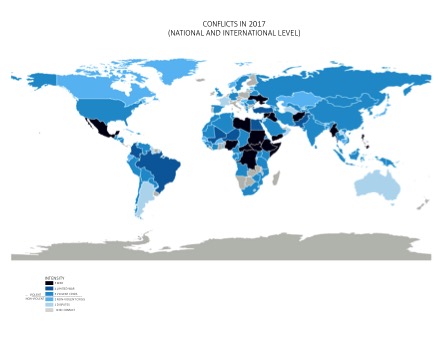

In this hybrid nature of violence from public security understanding frameworks or conflict approaches, we consider it an option to meet the criteria of the Conflict Barometer of the Heidelberg International Conflict Research Institute.[22]

Under the criteria of actors, measures and objects of conflict, the use of weapons, the actors involved, the causes, the destructive and life-threatening scope are analyzed, which allows criteria to be generated on intensities of conflict and levels of violence, considered as:

Low intensity non-violent conflicts

- Arguments

- Non-violent crises

Medium intensity violent conflicts

- Violent crises

High intensity violent conflicts

- Limited War

- War[23]

We are interested in calling attention, at this moment, that under this Barometer Mexico was considered in 2018 as the only country in all of America with a high intensity national violent conflict, that is, at war, due to the indexes of participants in the conflict, by the type of weapons (light and heavy) used, by the number of homicides, as well as the destruction of infrastructure, living spaces, economy and culture; generated by intrastate conflicts, involving state actors and organized groups (militia, police, ministerial, governors, etc.) and sub-state conflicts, in actions executed by civil or parastatal actors, which have produced a “limited war” under the Heidelberg Barometer in the fight between cartels and criminal organizations.[24]

GLOBAL MAP OF CONFLICT BAROMETER OF THE HEIDELBERG INTERNATIONAL CONFLICT RESEARCH INSTITUTE 2018.

In 2016 the reports of the CNDH (2016) and the UIA (2016) -as well as ourselves hazarded in I+D Magazine in 2015-[25] an attempt has been made to influence the controversy and the conflict of speeches, on the spatial production of said graves, through the creation of “recognition frameworks”[26] in which the clandestine grave is now a core part of our argumentation on studies and critical analysis of violence. Thus, from the “clandestine grave”, a term used by public security authorities to designate graves filled with the bodies of felons and criminals,[27] we have moved on to the activation of the term “clandestine common grave” to point directly to the produced and abandoned occlusion, as part of a reiterative process of violence in Mexico that activates both criminal groups and sub-state groups, as well as government agents.

MAP OF CLANDESTINE GRAVES IN MÉXICO 2007-2016.

IMAGE BY EJE CENTRAL JOURNAL. EDITORIAL IN HTTP://WWW.EJECENTRAL.COM.MX/PATROCINIO-CAMPO-DE-EXTERMINIO/

These clandestine graves are a spatial and temporal transformation in the forms of violence, which not only affects the material space, but also its scope of closer relationships and affective ties:[28] we are facing a transformation that has repercussions on a dissemination that is unmatched by previous experiences of family members, because spatial violence (such as the occurrence of the grave and the reflection itself on the forms of violence) opens a scope of crucial problems to the understanding of the humane in current times, and points directly to the singular irreplaceability, the uniqueness of each, therefore, the astonishing evidence that each violent action reifies, eliminates and deprives our singular and plural existence of space.

What we seek to highlight, in this context, is the fact that common graves have been produced, and are an integral part of a national violent conflict, whose highest percentage of executions occur by use of firearms. All of which indicates that the various actors, measures and objects of conflict (strategic positions, narcotics, human resources, natural resources or trafficking routes) produce dynamics of hostility, destruction and death in indexes similar to those experienced in Syria or Afghanistan.

Given the emergence of so much exposed violence we must ask and define what is a common grave? According to the UN it is an excavation that contains a multiple number of corpses, three or more.[29] However, here we must clarify that common grave refers to the simplest form of burial, of which there are vestiges from 120,000 years ago.[30] Minimal attention allows us to understand that the grave -as a deliberate action of burial- supposed a revolution in the human space. It was the collective creation of a specific space, a hole, hollow, concavity, incision and a place where bodies were deposited, often communally, as a continuity of the community of the living.[31] Structural occlusion of the dead body on earth or stone, but also an intimate relationship between spatialized memory and the affective bond in mourning, symbolized by inscriptions, funerary offerings and other symbolic details. In this way the common grave represented the vertical, underground incision of space in front of the horizontality of the landscape. A spatial infra-structure that not only required collective and voluntary efforts for the burial, but also the endeavor of its maintenance. In other words, a grave in this context is not only produced, but also taken care of and protected (pay attention to this tripartite signature of the grave, which runs through the history of the hindermost necropolitics: production, care and protection).

In this setting it seems important to go back to the first wonders of these spatial structures of the grave that are precursors of the tumulus, the corridor, the sarcophagus, the crypt; given that in all of them, the technical and symbolic capacity of the living to humanize the space of death is clear: nurturing a spatial-affective relationship between living and dying, between populating and commemorating.

At this point attention should be directed to the following delimitation: what is a clandestine grave? A cavity produced for the sake of spatial production under factors such as invisibility, anonymity and forgetfulness, a structure not only outside the law (criminal) but also against the flow of the relationship between production, care and protection of the dead. Similarly, far from the common grave dug in times of a health contingency (which can put the physical and/or mental health of the community at risk before the scattering of epidemics or natural disasters that the exposure of bodies may have an impact on mental health), as indicated by the World Health Organization,[32] contemplating risky situations and insisting on the respectful treatment of the disposed bodies at all times (that is, always in accordance with mortuary rites and customs, as well as with the informed consent of the community, either in relation to burial or incineration processes).

MULTIPLE BURIAL, TONCONICAL GRAVE, TLALPAN MEXICO CITY, 2500 B.C. PHOTO BY MAURICIO MARAT, INAH

The clandestine mass grave produced by malicious violence must not be homologated with the hoyancada (also enunciated as the huesa or hoya) that takes place in the civil space destined for it: the cemetery. In this case the hoyancada —a term in Spanish that serves here to distinguish the clandestine mass grave that we analyze— is a variation of the individual burial in a legitimate space, but in this case is available for the deposit of corpses that cannot be identified nor are they claimed. The hoyancada is opened and closed to receive the bodies without a name as part of its own infrastructural functions.

The concepts for referring to the graves found over and over in Mexico (in the period of 2007 to the present year), before invoking and involving the grave as a generating event of social suffering and public mournings, was marginalized into clandestinity, as part of the neutralization speeches of a war against organized crime that failed, amongst other things, by extending its level of execution of State violence towards a randomness in civil order (a lack of intelligence on behalf of the State in managing the force monopoly).

CLANDESTINE GRAVE WITH 8 CORPSES IN NAYARIT. FEBRUARY 13, 2018. PHOTO BY EFE

Thus, the term clandestine was part of a process of “immunization of violence” (Esposito, 2009: 109) as a secondary moment to failure: a process of neutralization, in which the enemies were the narco and the clandestine. To immunize the community: all this promoted by the instances of public security in the country and applied through mass media; therefore, in researching records it will be possible to notice that between 2007 to 2015 the graves previously spoken of as common began to be spoken of as clandestine.

Let’s summarize up to here. The common grave that we think of is the clandestine common grave, that cavity produced by the execution of the extreme violence that is homicide. The clandestine common grave is produced by the burial of more than three deposited bodies, and at the same time, such an infra-structure is produced as an act of collective coordination from the process of disappearance, homicide, transfer, opening of the cavity, disposal of the bodies and occlusion of said earth cavity. In addition, it must be considered that not only is it an integral part of an organized criminal process, but an exposure of a type of violence executed in the public space, that is, of reiterated violence: violence that directly damages not only the grave victims, but also the order of vital relationships that the situation of existence implies for each one (corporality-spatiality, temporality, co-relativity, meaning, history, legality, etc.). That is, the excavation whose opening seeks the definitive occlusion of the bodies, as well as its oblivion in the common space, will have to count on the meditation of pain that is constitutive (not derivative or sequential) of all acts of intentional homicidal violence, with the relationships and edges of those pains produced, not only in the immediate suffering subject, but also in the consideration and commotion of mourners that our relations extend to by our collective, human nexuses.

It is required, for that reason, to think of this event of the grave as a “broad conception of violence”, as called by Vittorio Bufacchi,[33] which is not reduced to the exercise of the executed force of the perpetrators on the victim. Violence in dimensions of spatiality and construction or destruction of space that we call “suffering space”: a space created by the relationships and interactions of pain and debt, generated by malicious homicidal violence that extends and intensifies between our spatial relationships in this which we call Mexico.

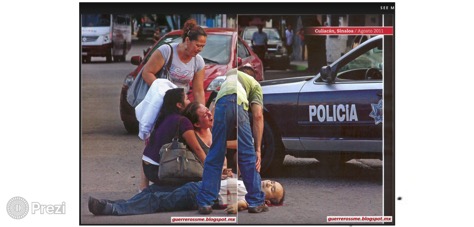

THIS IMAGE CHANGED THE PERSPECTIVE OF OUR ANALYSIS IN 2012, BECAUSE IT SHOWS A SUFFERING EXPOSURE WHICH INTERLACE TO THE DIFFERENT VICTIMS ALTERING THE SPACE IN ITS CONSTRUCTED COMPLEXITY. PHOTO IN PROCESO REVIEW, EL SEXENIO DE LA MUERTE, 2012.

In this sense, we must return to the first vestiges of common graves: they, as spatial practices of organization and dynamism, show that the cavities and incisions in the earth have appropriate dimensions for the bodies that inhabit them and are protective against the possibility of their trespassing. But beyond that, the graves express the relationships, functions and discourses of what a human body can do. Their rhythms, their amplitudes and frequencies, their samples and displays, allow us to know that the appropriation of space is given by the practice of the body, and that the appropriation of the body is given by spatial practice. In short, in the grave the body continues to claim space and it is the community of their own who propitiate it as an affective gesture, yes, of love, honor and recognition, in its production, care and protection.

MICENIC CIST 1400-1300 B.C. PHOTO BY NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

By contrast, the spatial infra-structure of intentional death that we face, the clandestine common grave, is a reality that goes beyond not only our theoretical discursivities, within the sciences, but also our cultural experiences. Because the common grave created by malicious violence brings into crisis homogeneous, homoloidal, isotropic, continuous, three-dimensional concepts such as emptiness, latitude, form, but, also, it questions us about space itself and about the spatial situation of our existence in relation to the earth as a possibility of being intervened. To be a-terrified, that is to say, deprived of that possibility is to be in a situation of suspense where rhythms and spatial practices are reduced.

In this sense, we refer to the distortion generated by the discourse that flows, squirming in legal, political and media jargon, a discourse that always arrives late in its limitations of what it cannot explain with criteria; or to the one who exceeds the resources of the geometric and topological language from the clandestine common grave, that is, the language that enunciates the clandestine common grave as a dump, as well as other emerging gramemas such as narco-graves, narco-cemeteries, which neutralize the grieving space, because they refer to a process of disqualification and disregard of the body, life and death in the victims as well as their mourners.

The absolute violence or brutality that testifies to the intensification of each discovery of a clandestine common grave in our near days, exposes the unacceptable suffering experienced by the torment and execution of which the victims were subject to; in addition, it exposes again and again the confirmation that these graves are productions that persevere in the frontal dissolution of individuality, the dislocation and the demolition of its memory; as well as the twisting of the considerations on the constitutive vulnerability of which we are not only mortal (as the Greek syllogism wanted) but we have become slavable in this country. Such modification is warned against not only on the threshold of the deprivation of life, of death; but consists of an absolute transmutation in which the corpse is at the same time instrument and object of debasement; transmutation that the funeral rites, historical cultural gains, sought to contain, to slow down, in a gradual transition undertaken in the disengagement of the other from this earth to go be between the earth and us, to be in-terred. Seminal backgrounds of our common memory, which contrast with the occlusion, oblivion and disappearance of the bodies, of our memory and of our ability to commemorate their death and their living.

ILLUSTRATION BY OLIVER McAINSH

The managing of killing is not reduced, therefore, to the materialization of taking life away, it extends to the affective assessment of how we understand our relationships among the living, and of the living with the dead in an extreme context of high intensity conflict, like the one that Mexico is at the center of right now. It would be about, in any case, making a thorough revision of our body categories, spatial relationships of life and death, and mourning.

One path that is proposed, a work hypothesis and a non-violence action path, in the face of clandestine graves is the reprocessing and assumption of collective forms to do public mourning and mourn the loss produced by homicidal violence (a mourning community); possibilities that were dismantled as a process of symbolic colonization in the New Spain period,[34] being reduced to family processes and domestic spaces, typical of an isolating modernity and inhibiting the public exhibition of pain.

FORENSIC WORKERS BURY ONE OF 40 UNIDENTIFIED BODIES AT THE SAN RAFAEL CEMETERY IN CIUDAD JUÁREZ, CHIHUAHUA STATE, MEXICO, ON JULY 23, 2018. PHOTOGRAPHY BY CARLOS SÁNCHEZ.

Clandestine common graves in Mexico, like other acts of malicious homicidal violence in the public space, are part of a major problem that demands measures to identify bodies, revolutions in legal frameworks, demands to political actors, accompanied by a frontal discussion where human sciences are points of critical attraction to question, neutralize, evidence and counteract discourses that socially channel forms of normalization, assumption or indifference to so much death and the inability to promote public mourning in the face of it.

To that end, and in contrast -as we have noted above-, the theoretical approach to the reiterability of the common clandestine grave, a possible one, is given from the referential frame of the critical space that gives guidelines to tend to the grave as an event of spatial interruption; which triggers considerations of the community from misery, pain, debt and mourners, that is, from the suffering space, and which allows us to question what country, what common land and territory can be built in the face of so much suffering and so many clandestine common graves.

Final Considerations

Throughout this collaboration we have highlighted the context of high intensity conflict that its inhabitants have been starring in Mexico for more than a decade. We tended to violence from a very particular spatial event: the clandestine common grave; we paused to distinguish this spatial production from others that can hold similarities (the “hoyancada” and common grave in case of health contingency); and in it, with a minimum approach, by contrast, we notice the astonishing cultural and historical emergency in the genealogy of the suffering void as a funeral process of estrangement from the dead in the production, care and protection of that particular space that was the burial. Given this, the grave of which we speak, shows that its production perseveres in the anonymity, abandonment and oblivion of the victimized. Added to this was the possibility of opening the category of violence towards a broad conception: where the act of force-damage affects not only the victim but also transgresses the affective relationships, the institutional, social and historical links that we maintain as creators of spatial experiences. We offer some interpretation keys on the reiterability of violence that intensifies and extends in our country, for which we identify this event as “clandestine common grave”; close to the conceptualization that the most recent literature has provided in reports such as the CNDH (2016) and the UIA (2016). Finally, we venture the possibility that, in the face of the clandestine common grave, a profound revision of the notions of collective mourning, forgotten in an infused way by a process of symbolic colonization in our cultural experiences, is needed; because in the face of the insistent repetition of murderous homicidal violence in the public space, which are common clandestine graves, it would be necessary to think about processes of interruption and non-repetition of this event as a construction of a culture of non-violence.

A MURDER VICTIM. PHOTOGRAPH: RODRIGO ABD/AP

Bibliography

- Agamben, Giorgio, ¿Qué es un dispositivo?, Anagrama, Barcelona, 2015.

- Aguirre, Arturo, Nuestro espacio doliente, reiteraciones para pensar en el México contemporáneo, Afínita, México, 2016, in https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303838171_Nuestro_espacio_doliente_Consideraciones_filosoficas_para_pensar_en_el_Mexico_contemporaneo_Our_Suffering_Space_Philosophical_Considerations_to_Think_about_Contemporary_Mexico

- Aguirre A. y Romero O., “Violencia expuesta, consideraciones filosóficas sobre el fenómeno de la fosa común”, Revista I+D, No. 9, Chiapas, pp. 82-107, in http://www.espacioimasd.unach.mx/articulos/num9/espacioimad9_violencia_expuesta.php, 2015.

- Amnesty International, Informe 2016/17, Amnistía Internacional. La situación de los derechos humanos en el mundo, Amnesty International, Londres, 2017.

- Astorga, L., “Estado, drogas ilegales y poder criminal. Retos transexenales”, Letras Libres, No. 167, Ciudad de México, pp. 1-6, in https://www.letraslibres.com/mexico/estado-drogas-ilegales-y-poder-criminal-retos-transexenales.

- Bernstein, Richard, Pensar sin barandillas, Gedisa, Barcelona, 2015.

- Bovero, Michelangelo, “Lugares clásicos y perspectivas contemporáneas sobre política y poder”, en Bobbio N. et al., Origen y fundamentos del poder político, Grijalbo, México, 1985.

- Bufacchi, Vittorio, “Dos conceptos de violencia”, en A. Aguirre (comp.), Estudios para la no-violencia I. Pensar la fragilidad humana, la condolencia y el espacio común, 3 Norte-Afìnita, Puebla, 2015.

- Butler, Judith, Precarious Life. The Power of Mourning and Violence, Verso, Brooklyn, 2006.

- _______, Marcos de guerra. Las vidas lloradas, Paidós, México, 2010.

- Calleja, Eduardo, La violencia en la política. Perspectivas teóricas sobre el empleo deliberado de la fuerza en los conflictos de poder, CSIC, Madrid, 2012.

- Cavarero, Adriana, Horrorismo: nombrando la violencia contemporánea, Anthropos-UAM, Barcelona, 2009.

- Cavarero, A., Nombrando la violencia contemporánea, Anthropos, Barcelona, 2009.

- Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos (CNDH), Informe especial de la Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos sobre desaparición de personas y fosas clandestinas en México, in http://www.cndh.org.mx/sites/all/doc/Informes/Especiales/InformeEspecial_20170406.pdf, 2016.

- Escalante, Pablo, “La casa, el cuerpo y las emociones”, Historia de la vida cotidiana en México, Colmex, México, 2004.

- Esposito, Roberto, Comunidad, inmunidad y biopolítica, Herder, Barcelona, 2009.

- Etienne, G. Krug et al., Informe mundial sobre la violencia y la salud, OMS, Washington D.C., 2002.

- Franco, Jean, Cruel Modernity, Duke University Press, Durham, 2013.

- Fuentes, Antonio, “Necropolítica y excepción. Apuntes sobre la violencia, gobierno y subjetividad en México y Centroamérica”, en A. Fuentes, Necropolítica. Violencia y excepción en América Latina, BUAP, Puebla, 2012.

- Graña, Daniel, “El llorar entre los nahuas y otras culturas prehispánicas”, Estudios de cultura Náhuatl, No. 40, Ciudad de México, 2003, pp. 155-174, en http://www.historicas.unam.mx/publicaciones/revistas/nahuatl/pdf/ecn40/823.pdf

- Gregory, Daniel al., Violent Greographies, Routledge, New York, 2007.

- Guerrero, E., “¿Bajó la violencia?”, en Nexos, No. 444, México, 2015, pp. 21-28, in https://www.nexos.com.mx/?p=24035

- Guilaine J. y Zammit J., El camino de la Guerra. La violencia en la prehistoria, Ariel, Barcelona, 2002.

- Heidegger, Martin, Construir Habitar Pensar en Filosofía, Ciencia y Técnica, Universitaria, Santiago Chile, 2003.

- Heidelberg Institute for International Conflict Research (HIIK), Conflict Barometer 2017, Heidelberg, HIIK, 2018 in https://www.hiik.de/en/konfliktbarometer/pdf/ConflictBarometer_2017.pdf.

- Huffschmid, Anne, “Huesos y humanidad. Antropología forense y su poder constituyente ante la desaparición forzada”, Athenea Digital, No. 3, Barcelona, 2015, pp. 195-214, in http://dx.doi.org/10.5565/rev/athenea.1565

- Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP), Índice de paz positiva, IEP, México, 2017.

- Keane John, Reflexiones sobre la violencia, Alianza, Madrid, 2000.

- Lara, Catalina, “Fosas Clandestinas”, El universal, 2014, in http://www.eluniversal.com.mx/graficos/graficosanimados14/EU_Fosas_Clandestinas/.

- Lefebvre, Henry, La producción del espacio, Capitán Swing, Madrid, 2013.

- Llorente, Marta, La ciudad: huellas en el espacio habitado, Acantilado, Barcelona, 2015.

- Madrid, Antonio, La política y la justicia del sufrimiento, Trotta, Madrid, 2010.

- Massey, Doreen, Un sentido global de lugar, Icaria, Barcelona, 2012.

- Mazowiecki, T., “Annex I. Summary of the Report of the Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions on his Mission to Investigate Allegations of Mass Graves from 15 to 20 December 1992”, en Report on the Situation of Human Rights in the Territory of the Former Yugoslavia, 10 de febrero de 1993, UN, New York, in http://repository.un.org/bitstream/handle/11176/212952/E_CN.4_1993_50-EN.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y

- Morbiato, C. “Prácticas resistentes en el México de la desaparición forzada”, Trace, No. 71, Ciudad de México, 2016., pp. 137-164, in https://doi.org/10.22134/TRACE.71.2017.100

- Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS), Aplicación de las recomendaciones del Informe mundial sobre la violencia y la salud, París, OMS, 2003, in http://apps.who.int/gb/archive/pdf_files/WHA56/sa5624.pdf?ua=1

- Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS), Informe sobre la violencia y la salud, Washington D.C., OMS, 2003.

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud (OPS), Informe sobre la situación mundial de la prevención de la violencia 2014, OPS, Washington D.C., 2016, in https://oig.cepal.org/sites/default/files/informe_sobre_la_situacion_mundial_de_la_prevencion_de_la_violencia.pdf

- Ovalle, Lilian Paola et al., “Pensar la memoria desde la frontera: recuerdo, reconstrucción y reconciliación en el caso del ‘pozolero’”, Contracorriente, 1, s.l., 2014, pp. 278-300, in https://acontracorriente.chass.ncsu.edu/index.php/acontracorriente/article/download/1333/2248/.

- Pereda, Carlos, La filosofía en México en el siglo XX. Apuntes de un participante, CONACULTA, México, 2013.

- Editorial Proceso, El sexenio de la muerte, Proceso, Edición especial, ciudad de México, 2012.

- Reguillo, Rossana, “De las violencias: caligrafía y gramática del horror”, Desacatos, No. 40, Guadajalara, 2012, pp. 36-46, in http://desacatos.ciesas.edu.mx/index.php/Desacatos/article/view/254/134

- Riekenberg, M., Violencia segmentaria. Consideraciones sobre la violencia en la historia de América Latina, Iberoamericana, Madrid, 2015.

- Rodrigo, J., Una historia de la violencia. Historiografías del terror en la Europa del siglo XX, Anthropos-UAM, México, 2017.

- Rosenblatt, Addam, Digging for Disappeared. Forensic Science after Atroticy, Standford University Press, California, 2015.

- Salama, Pierre, “Informe sobre la violencia en América Latina”, Revista de Economía Institucional, No. 18, l., 2008, pp. 81-102, in https://www.economiainstitucional.com/pdf/No18/psalama18.pdf

- Sánchez, Vázquez, Adolfo, El mundo de la violencia, UNAM-Fondo de Cultura Económica, México, 1998.

- Serrano de Haro A., Cuerpo vivido, Encuentro, Madrid, 2010.

- Secretariado Ejecutivo del Sistema Nacional de Seguridad Pública (SESNSP), Informe de víctimas de homicidio, secuestro y extorsión 2017, SESNSP, México, 2018, in http://secretariadoejecutivo.gob.mx/docs/pdfs/victimas/Victimas2017_012018.pdf,

- Staudigl, Michel, Phenomenologies of Violence (Vol. 1), Brill, Boston Mass., 2014.

- Trejo, Guillermo. y Ley, Sandra, “Municipios bajo fuego”, Nexos, No. 444, Ciudad de México, 2015, pp. 30-37.

- UIA, Violencia y terror. Hallazgos sobre fosas clandestinas en México, Comisión Mexicana de Defensa y Promoción de Derechos Humanos-UIA, México, 2016, in http://www.ibero.mx/files/informe_fosas_clandestinas_2017.pdf

- Villoro, Luis, De la libertad a la comunidad, Fondo de Cultura Económica, Madrid, 2001.

- Waldenfels, B., “Habitar corporalmente el espacio”, en Daimón. Revista de filosofía, No. 32, Madrid, 2004, pp. 24-37, en http://revistas.um.es/daimon/article/view/15221/14681

- World Bank, How Communities Manage Risk of Crimea and Violence, World Bank, Washington D.C. 2013.

- World Health Organization (WHO), Disposición final de los cadáveres después de una emergencia, Guía técnica No. 8, WHO, l., 2009, in http://www.disaster-info.net/Agua/pdf/8-DisposicionFinalCadaveres.pdf

- Zabludovsky, K., Nadie sabe cuántas fosas comunes hay en México. Mucho menos el gobierno, March 27, California, 2015, in http://www.buzzfeed.com/karlazabludovsky/nadie-sabe-cuantas-fosas-comunes-hay-en-mexico-mucho-menos-e#.gnB83alGb

Notas

[1] This paper is part of the project “Forensic Philosophy: Reflections on Space, the Body and Homicide in Contemporary Mexico”, registered in the Postgraduate Program in Contemporary Philosophy of Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, Mexico.

[2] Fuentes Díaz, Necropolítica y excepción. Apuntes sobre la violencia, gobierno y subjetividad en México y Centroamérica, pp. 34-38.

[3] Gutiérrez Guerrero, “¿Bajó la violencia?”, pp. 21-28.

[4] Villoro, De la libertad a la comunidad, p. 19.

[5] Butler, Precarious Life, pp. 19-49.

[6] Bovero, Lugares clásicos y perspectivas contemporáneas sobre política y poder, pp. 48-56.

[7] Reguillo, De las violencias: caligrafía y gramática del horror, pp. 36-46.

[8] Pereda, La filosofía en México en el siglo XX. Apuntes de un participante, p. 323.

[9] Agamben, ¿Qué es un dispositivo?, p. 22.

[10] Cf. Proceso, “El sexenio de la muerte”, passim.; Trejo et al., “Municipios bajo fuego”, pp. 30-36.

[11] González Calleja, La violencia en la política, pp. 21-57.

[12] Up until December 2017, the criminal traffic light indicated that this year was the most violent year, with 19,057 homicides from January to November 2017. This indicates an increase of 23% in relation to 2016 (visit http://www.semaforo.com.mx/Semaforo/Incidencia). Recently with an average of 20.51 intentional homicides per 100 thousand inhabitants in Mexico in 2017 (total: 29,159 murders) (SESNSP, 2018), as a result of interpersonal violence, violent conflicts by territory, violence between gangs and murders (the fact that this violence is not motivated by political ideologies or religious, but by the dispute of sources, networks and routes of economic-political capitalization is highlighted), we can speak of an increase that returns to the figures of 2013, but that has extended to more municipal locations, 407 in 2016 (see the entry “ Deaths by homicide” in the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI), at http://www.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/olap/proyectos/bd/continuas/mortalidad/defuncioneshom.asp?s=est).

[13] Amnesty International, La situación de los derechos humanos en el mundo, pp. 307-311.

[14] Massey, Un sentido global del lugar, p. 161.

[15] Lefebvre, La producción del espacio, pp. 129-132.

[16] Heidegger, Construir, habitar, pensar en filosofía, p. 199.

[17] The reiteration of violence carried out in the spatial structure of the common grave can be supported by the re-count of the following events: between 2010-2011 in the Municipality of San Fernando, Tamaulipas, 196 bodies were found in clandestine graves; in 2011 Tijuana was the star of the extraordinary clandestine grave, in which bodies were counted by liters (17,500 liters approximately) in which between 300 and 650 bodies were disintegrated by Santiago Meza, aka El pozolero; between 2011-2012 five municipalities of Durango provide information about having generated 15 common graves which contained 351 bodies; between 2013-2014 the municipality of La Barca, Jalisco (on the border with Michoacán), between November and January, 74 bodies were recovered when the search for two kidnapped federal policemen was undertaken; between 2014-2015 in the municipality of Iguala, Guerrero, in the search for Ayotzinapa’s 43, 129 bodies were recovered from exposed illegal burial sites thanks to the search brigades; in 2016 in the municipality of Tetelcingo, Morelos, we learned of the clandestine common grave created between 2010-2013 under the illegal action of the State Attorney General in which 119 bodies were buried; that same year, in the municipality of San Pedro de las Colinas, Coahuila, Ejido el Patrocinio, the clandestine common grave created between 2007-2012 was exposed, and pinpointed by the media as “an extermination camp”, in which the amount of bodies is undetermined due to the conditions of the finding and by the slow processing of information of more than 4,500 skeletal remains. Finally, in this account of the horror of this spatial structure, in 2017, Colinas de Santa Fe, Veracruz, was the place where 253 corpses were recovered (to support these findings see CNDH, 2016; UIA, 2016 and Zabludovsky, 2015).

[18] Cf. CNDH, Informe especial de la Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos sobre desaparición de personas y fosas clandestinas en México, pp. 450-513.

[19] Cf. Zabludovsky, “Nadie sabe cuántas fosas comunes hay en México. Mucho menos el gobierno”, passim.

[20] Astorga, “Estado, drogas ilegales y poder criminal”, p. 3.

[21] Franco, Cruel Modernity, p. 25.

[22] Vid., Heidelberg Institute for International Conflict Research (HIIK), Conflict Barometer 2017.

[23] Ibid., pp. 7-9.

[24] Ibid., pp. 17-19.

[25] Vid. Aguirre et al., Violencia expuesta, consideraciones filosóficas sobre el fenómeno de la fosa común, passim.

[26] Butler, Marcos de Guerra. Las vidas lloradas, pp. 19-29.

[27] Lara et al., Fosas Clandestinas, passim.

[28] Rosenblatt, Digging for the Disappeared. Forensic Science after Atrocity, pp. 54-58.

[29] Mazowiecki, “Annex I. Summary of the Report of the Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions on his Mission to Investigate Allegations of Mass Graves from 15 to 20 December 1992”, pp. 59-60.

[30] Jean Guilaine et al., El camino de la Guerra. La violencia en la prehistoria, pp. 61-100.

[31] Llorente, La ciudad: huellas en el espacio habitado, pp. 65-67.

[32] World Health Organization (WHO), Disposición final de los cadáveres después de una emergencia, passim.

[33] Bufacchi, “Dos conceptos de violencia”, pp. 21-22.

[34] Vid. Graña Behrens, “El llorar entre los nahuas y otras culturas prehispánicas”, passim. Also review Escalante, “La casa, el cuerpo y las emociones”, pp. 255-260.